Author: Zara Zayna Hossain – Bangladesh – PROMPT! Cohort #1

Introduction:

Imagine waking up in your bedroom where the walls are alive, the air smells fresh with herbs, and sunlight filters through leafy canopies growing along the sides of your corridors. A house where birds flit across rooftop gardens, and you can pluck fresh tomatoes or kale for breakfast. This isn’t a scene in a sci-fi movie; it’s the emerging reality of living architecture.

For most of history, architecture has focused on strength and protection. Concrete, steel, and glass gave us buildings that could stand tall against time and weather, but did very little in nurturing us and often shut us off from the natural world. Today, however, architects and scientists are beginning to imagine something different: cities designed as living systems. This vision, known as living architecture, extends beyond mere shelter. It brings together ideas such as urban farming, biophilic design, and even self-healing materials to create spaces that not only protect us but also actively help us thrive (The Living, 2024). These buildings breathe with us, grow with us, and even give back to the planet by supporting ecosystems around them.

The future of our planet is not just green rooftops or energy-efficient walls. It is walls that heal their own cracks, facades that filter the air, and rooftops that produce our food. In other words, buildings that are alive.

The Science Behind Living Architecture

At the heart of every living architectural creation, there are materials and technologies that make the buildings regenerate and heal like us.

Self-healing materials: Concrete infused with bacteria can seal its own cracks when exposed to moisture (Van Tittelboom, De Belie, Van Loo, & Jacobs, 2011). Mycelium- the root system of fungi can be grown into lightweight, biodegradable bricks that are both strong and compostable (The Living, 2014). Together, they reduce maintenance costs, extend building lifespans, and decrease the environmental impact.

(An Example of Cracked Concrete Healing with Bacteria)

(Fungi-based blocks)

Air-Purifying facades: Algae panels on walls or windows absorb CO₂, which generates oxygen, and even yield biomass for energy. One example of this is the BIQ Building of Hamburg (Case studies on BIQ Building Hamburg). Vertical plant systems inside buildings clean toxins and regulate humidity, converting stale air into nearly a whiff of fresh forest air, for example, the Spain Algae Bioreactors.

(Algae- facade Panels in BIQ Building, Hamburg)

Urban farming as infrastructure: Rooftop gardens, hydroponic towers, and vertical farms bring a large amount of food production into our cities. A 2022 study across 53 countries found that some urban farms can yield two to four times more produce per square meter than conventional agriculture (Payen et al., 2022). In a hydroponic system, the greens reach the harvesting stage in the same period as that of soil farms, but use up to 95% less water because the water is recirculated and losses are minimized. (Pomoni et al., 2023). These also regulate building temperature, reduce the urban heat island effect, and cut

transport emissions.

(Example of modern city farming system)

Combined with green roofs, passive heating and cooling, and water recycling, living architecture becomes a self-sustaining ecosystem that supports both life inside its walls and biodiversity outside them.

Healing Spaces: Architecture for Human Well-Being

Living buildings don’t just sustain the environment; they heal us, too.

Environmental psychology has long shown that light, air, and spatial design shape our mood, cognition, and stress levels. One landmark study found that patients recovering from surgery with views of trees healed faster and needed fewer painkillers than those whose windows faced a brick wall (Ulrich, 1984).

Now imagine bringing these principles of Biophilic Design into our everyday spaces:

- A student who walks through a sunlit corridor lined with flowing vines will feel calmer before an exam, which can lead to better academic performance.

- A cancer patient at Maggie’s Centers in the UK sits in a garden courtyard, drawing strength from greenery that softens the fear of a life-threatening treatment (Case studies on Maggie’s Centre architecture).

- Office workers can harvest their own herbs from a vertical wall during lunch break and reconnect with the rhythm of nature.

Gardening activities in school and residential complexes also foster social bonds, responsibility, and mental resilience. This practice also adds artistic layers to our homes. Colors inspired by forests, textures that mimic bark and stone, and flowing organic patterns transform sterile and boring spaces into a soulful environment.

Beyond modern psychology, many ancient traditions also recognize how spaces can influence human well-being:

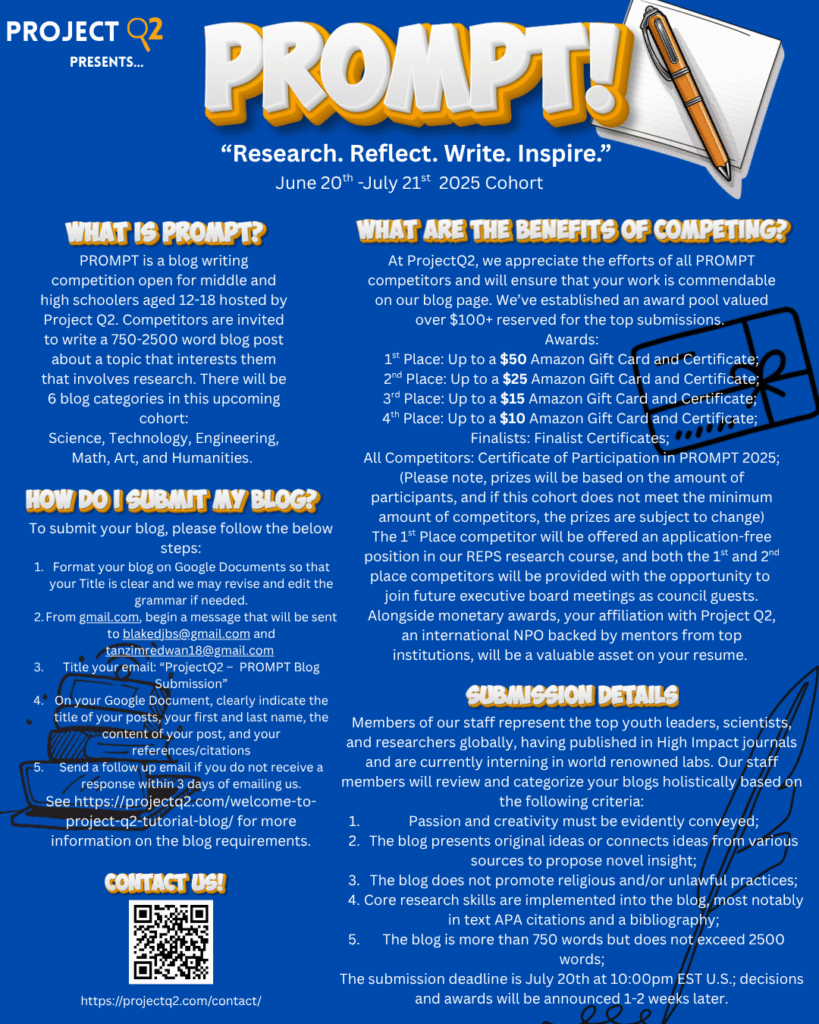

- Feng Shui, an ancient Chinese practice that aims to harmonize different individuals with their environment by strategically arranging objects and spaces to optimize the flow of positive energy known as Chi. It emphasizes the five elements- Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water, creating a natural balance (Mak & Ng, 2005).

(The Cycle of Feng Shui)

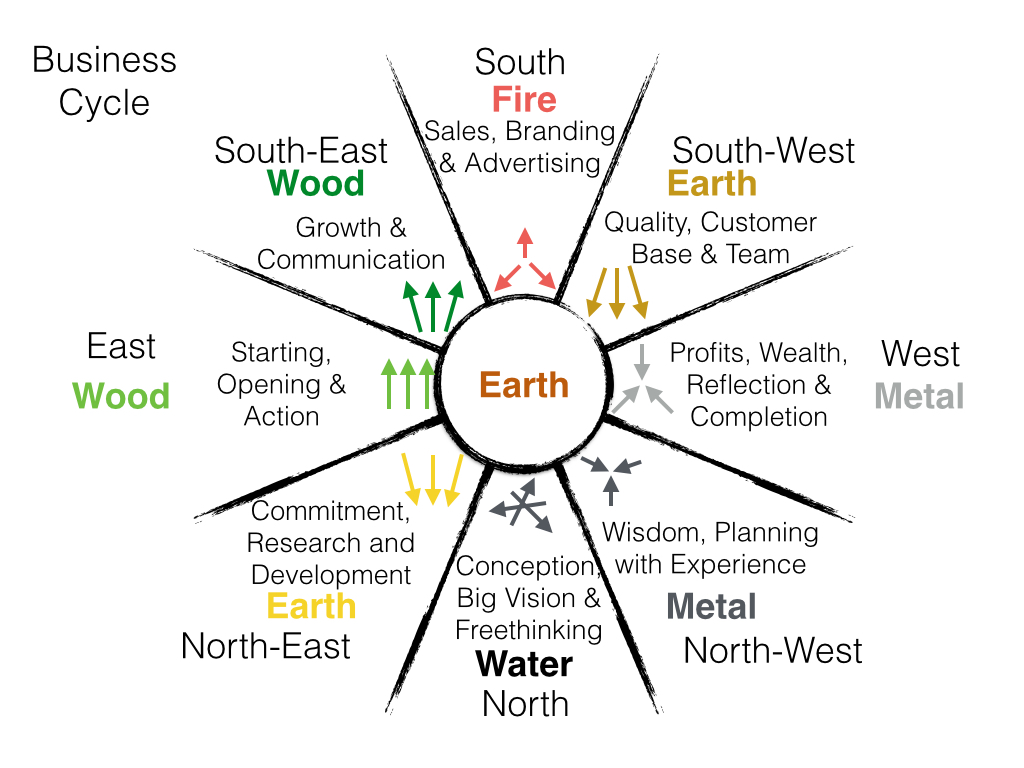

- Vastu Shastra, an ancient Indian system of architecture, focused on aligning buildings with the five elements of nature (earth, water, fire, air, and space) to promote health, peace, and prosperity (Dagens, 2007).

(The Diagram for Vastu Shastra)

Both traditions show that the idea of healing spaces is not new; living architecture is, in many ways, a modern scientific contribution to these ancient and timeless practices.

Historical Roots of Living Architecture

Though Living Architecture might sound futuristic, it actually has deep historical roots.

- Japanese Zen Gardens: These gardens used stone, water, and plants in minimalist forms to promote peace and meditation (Nitschke, 1993). Modern architects often adapt these principles to create quiet, healing country yards in hospitals and schools.

( Zen Gardens)

- Persian Gardens: These gardens were designed as “paradise on earth”, blending water channels, shade trees, and geometry to provide comfort in hot climates (Moynihan, 1979).

(Persian Gardens)

- Roman Atriums: These marvelous innovations brought sunlight, air, and sometimes even small gardens into the centers of homes, centuries before biophilic design became a buzzword (Jashemski, 1979).

(Roman Atriums)

- Aztec Chinampas: In ancient Mexico, floating gardens that combined settlements with food production are early examples of urban farming integrated into architecture (Coe & Koontz, 2013).

(Aztec Chinampas)

The traditions prove that the desire for living and breathing buildings is not new to humankind. What’s new is the technology that allows us to scale them across modern cities.

The Intersection: Living Architecture That Heals and Grows

When science, art, and psychology converge, buildings become ecosystems that nourish our body, mind, and community.

Here are some spectacular examples of living architecture:

- Bosco Verticals in Milan hosts 900 trees and 20,000 plants across two towers, improving both air quality and urban biodiversity (Boeri, 2014).

(The Bosco Verticals in Milan as an example of vertical forest towers)

- The Eden Project in the UK immerses visitors in giant biomes that educate and inspire us about sustainability(Eden Project, n.d.).

( Eden Project in the UK, where plants grow inside a giant biome)

- Maggie’s Centers blend gardens, natural light, and spatial flow in healing sanctuaries for patients(Case studies on Maggie’s Centre architecture).

(Maggie’s Centers)

Now imagine extending these ideas citywide:

- Apartment blocks where edible walls grow spinach and strawberries.

- Schools where rooftop farms double as classrooms, teaching children science and stewardship.

- Streets lined with green corridors that filter pollution, cool the air, and invite birds back into the city.

- The use of smart sensors that can monitor plant health and air quality, ensuring buildings adapt to human comfort as much as environmental needs.

In places, residents breathe easier, harvest their meals, and heal faster. And all this happens within the same living, breathing architecture.

Challenges and Considerations

This vision is inspiring, but it also comes with its own challenges.

- Cost & expertise: Self-healing materials and hydroponic systems remain more expensive than conventional construction. Maintenance also requires skilled knowledge (Van Tittelboom et al, 2011).

- Urban planning: Retrofitting older buildings in complex areas often lags behind innovation, as zoning laws can be slow to adapt.

- Equity: The risk is creating green “luxury oases” that are accessible only to the wealthy. For living architecture to truly heal, access to green, regenerative spaces must be inclusive and affordable.

So, balancing innovation with accessibility is the next frontier.

Solutions: Scaling Living Architecture

These challenges are indeed real, but they are not insurmountable.

- Lowering costs: just as solar panels dropped in price through research and mass adoption, biomaterials and hydroponic systems can become affordable with investment and innovation.

- Policy support: Cities can offer tax incentives, green credits, or fast-track permits for buildings that integrate living systems.

- Community-driven models: Rooftop farms can be co-managed by residents, schools, or local cooperatives, turning maintenance into shared stewardship.

- Education & training: Universities and vocational programs can prepare a new generation of architects and engineers skilled in bio-design and sustainable farming (Payen et al., 2022).

By combining technology, policy, and community, we can make living architecture not just visionary but practical and accessible to all.

Our Little Roof-top Farm:

For me, living architecture isn’t just a concept—it’s a daily reality on my own rooftop. My family has turned our rooftop into a lush green oasis, overflowing with fruit trees, vegetables, and herbs. We grow plants in recycled plastic paint buckets and water drum barrels, giving new purpose to discarded plastics and transforming them into tools that benefit both the environment and our lives.

Each morning, stepping outside, I’m welcomed by the invigorating scent of fresh mint, the golden glow of ripening papayas, and the gentle hum of bees and butterflies at work.

(Some Pictures of our Roof-top)

While our rooftop isn’t a futuristic skyscraper in Milan or a high-tech algae façade in Germany, it proves how even simple rooftop gardens can completely transform a home. The greenery cools the rooms below, provides a steady supply of fresh produce, and creates a retreat where we can truly breathe. In its own way, it makes our house feel vibrantly alive.

Conclusion

Living architecture is no longer a futuristic fantasy; It’s happening right now. From bacteria-infused concrete to vertical forests, these innovations show us that buildings can heal humans, nourish communities, and regenerate ecosystems.

The cities of tomorrow really don’t have to be gray, silent, or sterile. They can also breathe, grow, and inspire. The walls around us don’t have to trap us; Instead, they can nurture our lives, heal our minds, and sustain the planet.

Now, the question is not whether we can build such spaces, but whether we choose to.

Reference List (APA Style)

· Boeri, S. (2014). Bosco Verticale: A home for trees that houses humans. Milan: Corraini Edizioni.

· Payen, F. T., Evans, D. L., Falagán, N., Hardman, C. A., Kourmpetli, S., Liu, L., … & Davies, J. A. C. (2022). How much food can we grow in urban areas? Food production and crop yields of urban agriculture: A meta-analysis. Earth’s Future, 10(8), e2022EF002682. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF002682

· Ulrich, R. S. (1984). Viewing through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420–421. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402

· Van Tittelboom, K., De Belie, N., Van Loo, D., & Jacobs, P. (2011). Self-healing efficiency of cementitious materials containing tubular capsules filled with a healing agent. Cement and Concrete Composites, 33(4), 497–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2011.01.004

Pomoni, D. I., Koukou, M. K., Vrachopoulos, M. G., & Vasiliadis, L. (2023). Energies, 16(4), 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16041690

Eden Project. (n.d.). Designing sustainable biomes. Retrieved from https://www.edenproject.com

Case studies on BIQ Building Hamburg for algae facades, Maggie’s Centre architecture reviews.

Feng Shui: Mak, M. Y., & Ng, S. T. (2005). The art and science of Feng Shui—a study on architects’ perception. Building and Environment, 40(3), 427–434.

Vastu Shastra: Dagens, B. (2007). Mayamatam: Treatise of Housing, Architecture and Iconography. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

· Zen Gardens: Nitschke, G. (1993). Japanese Gardens: Right Angle and Natural Form. Taschen.

Moynihan, E. B. (1979). Paradise as a garden in Persia and Mughal India. George Braziller.

Jashemski, W. F. (1979). The gardens of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the villas destroyed by Vesuvius. Caratzas Brothers.· Hy-Fi Mycelium Tower: The Living. (2014). Hy-Fi: MoMA PS1 Young Architects Program.